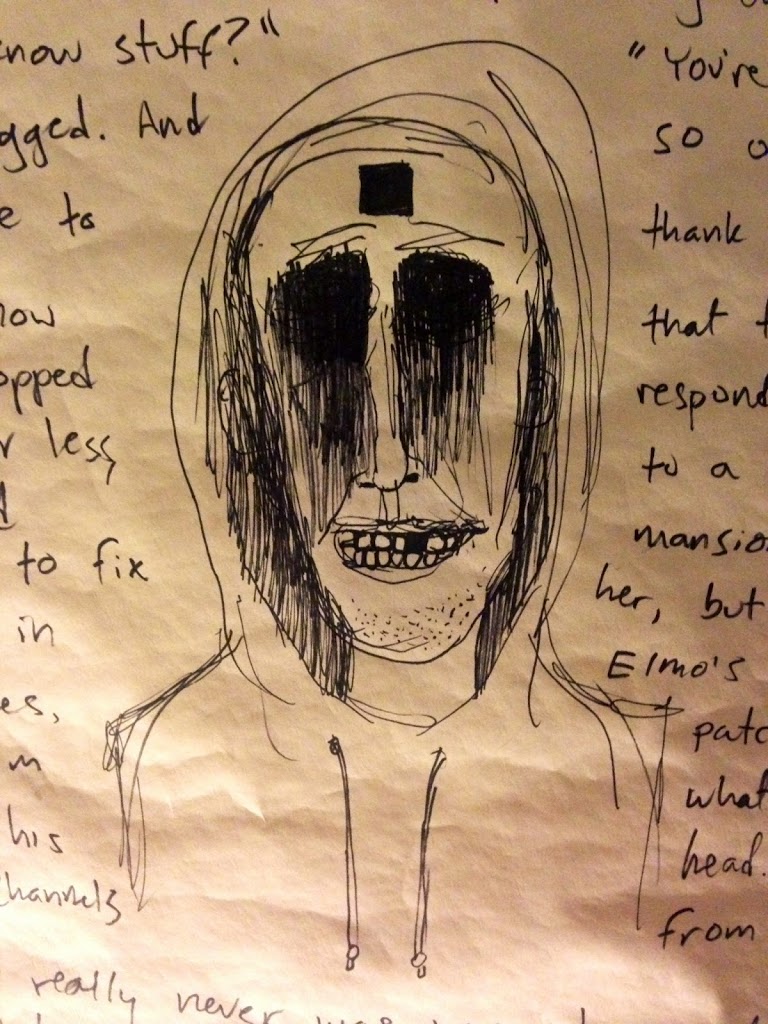

Roger has five fingers on each hand, and two eyes. He has skin. He wears clothes that cover his skin. His fingernails grow at the usual rate. He has the same number of feet as he has legs, which is two. His heart beats often, causing his blood to circulate. Yes, Roger is in every way an ordinary human person.

Roger is not from this city. He was born in a different city, where his family and anyone else who might have known him for more than two years must surely live. Now he lives in an apartment, alone. The apartment has a kitchen and a bathroom, as well as a bedroom. He uses all of these, for their intended purposes.

Roger works in a glue factory. He does not take unseemly pleasure in the deaths of horses. His job is to scalp the horses that are dead. It is an unremarkable, even tedious job. Roger often talks on the phone. In these conversations he is mostly silent. Occasionally he says the names of colors, such as “black,” or “red” or “dark red.” They are ordinary colors, as might be found in a box of crayons.

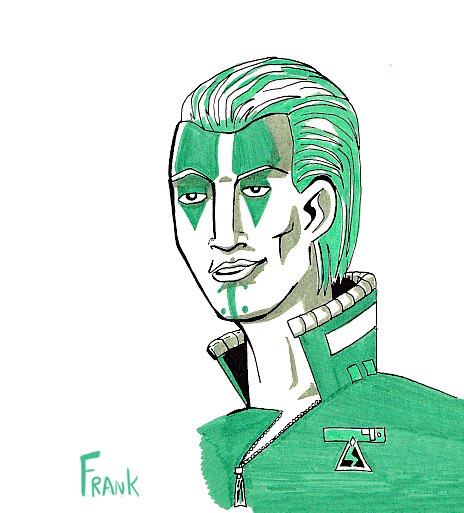

Roger is not a spy. He is not from another planet. He is not a creature wearing a human skin, or else we are all creatures wearing a human skin. He is not planning anything. He is not informing anyone. He is not going anywhere. He is nothing. He is not important. Don’t worry about it.