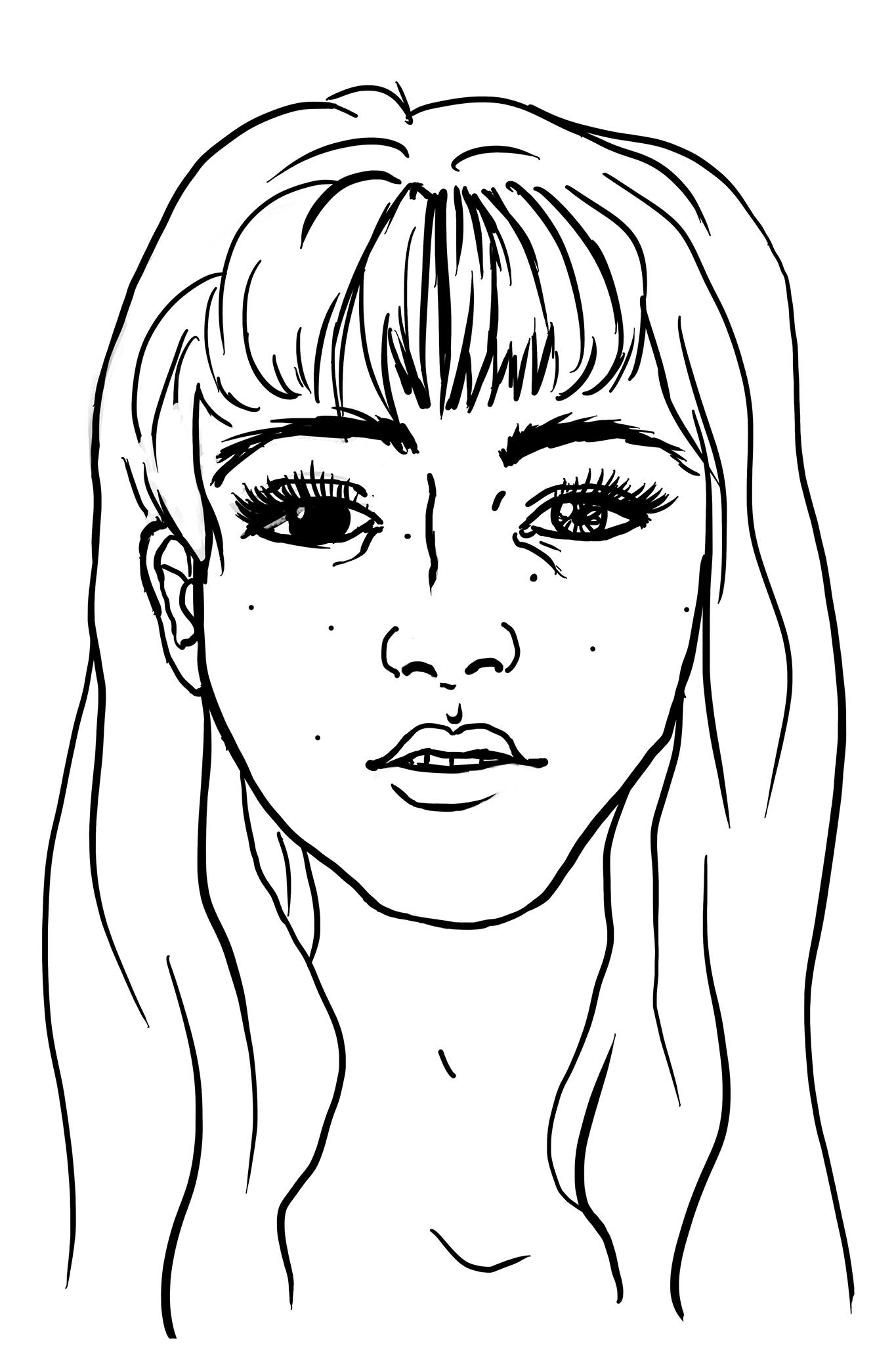

The children he works for have tried to call him many things: Gordon, or Gordie, or Go-Go, or Gor. To each of these he gives a not-quite-smile, an almost-shake-of-the-head, and a serious look straight in the eyes.

“It’s Mister Bear, if you please,” he says.

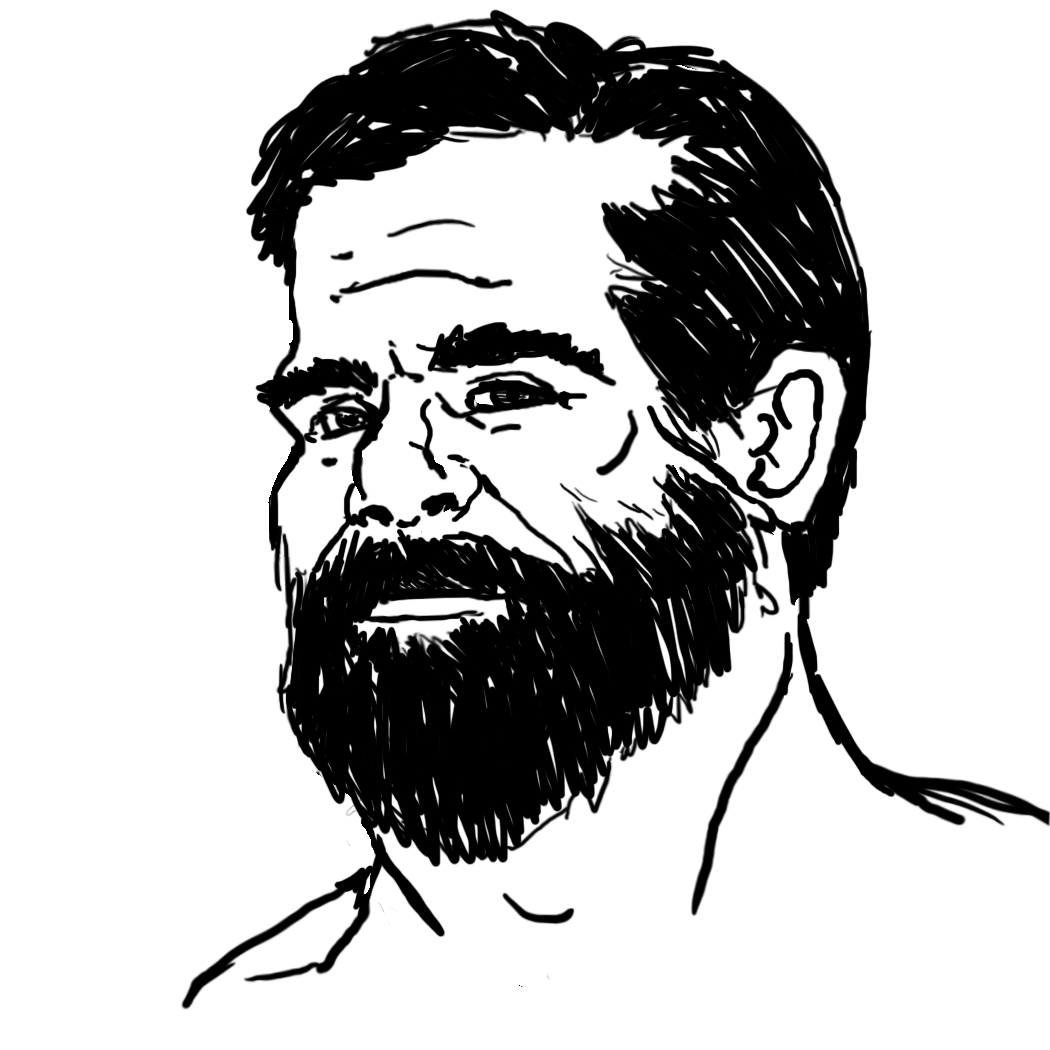

What an adult might interpret as aloofness somehow only makes him more beloved by the children. Perhaps it’s because the name upon which he insists is exactly what a child might name her favorite stuffed toy. Perhaps it’s due to his storybook physique – rosy-cheeked and neckless, round and mountainous, heavy muscles hidden beneath his trench coat. Whatever the reason, the children fling themselves at him when he arrives each morning, their arms making it barely a third of the way around his waist. Each night they weep theatrically at his departure. And in between, whether at school or the mall or the barber shop, they never stray far from his side. This is good for Gordon; it makes his job easier.

Somewhere between the police and the war, the resistance and the smuggling and the contract killings, Gordon realized that he was a violent person. In the same way that some people have a sexual awakening, Gordon realized the simple fact of his own brutality. He’s good at killing people, and he likes to be good at things. Killing causes a host of problems, to be sure, but most problems caused by killing can be solved by more killing, if you take the long view, which Gordon does. He went through periods of denial, of course, where he swore off violence altogether, but ultimately his thick, squarish fingers, his palms dense as lead, aren’t good for any other kind of work. He finally had to accept that he will never make more than six months without at least hurting someone very, very badly. And if he’s going to hurt people regardless, he’d rather hurt people who want to hurt children.

The people who pay Gordon aren’t good people, but he doesn’t protect those people. He protects their children, and their children are good because they are children. He is always on time. He speaks only when spoken to, or when there is an emergency, but if a child asks him a question he always does his best to answer. If he can’t answer a question immediately, he will go home and look up the answer in his encyclopedia. He buys the children presents for Christmas and their birthdays – a stuffed pig or a pair of nice wool gloves, but never a popgun or a wooden sword. He is the only weapon they will ever need, he hopes.