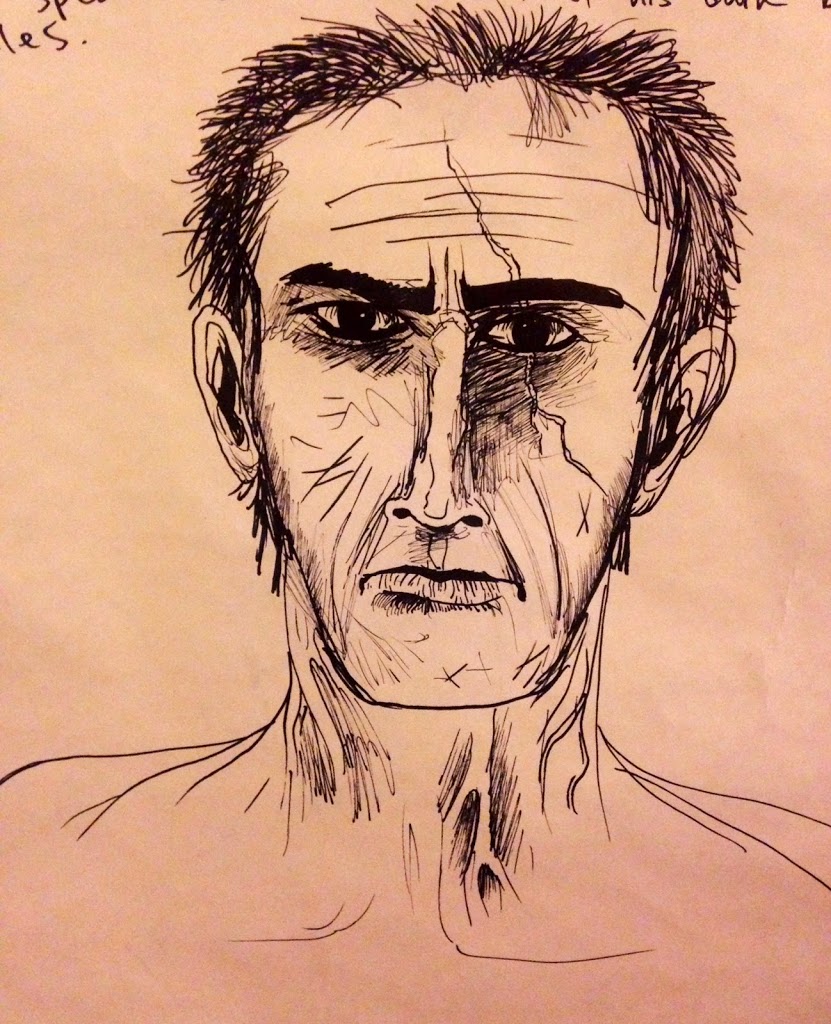

Elmo was never very observant. His sister always told him so. And he never resented her for it – merely took it the way he took all his sister’s sayings: as truths he was powerless to change. She told him he was too trusting, too. He shrugged and smiled, gap toothed from a bully’s skateboard to the face.

“You’re right,” he said. “But what am I gonna do about it? Not trust people? I can’t not trust people. If I stopped trusting one person, I’d have to stop trusting everyone to be fair, and then how would I know stuff?”

“You’re too fair, too.” Said his sister. And he shrugged. And so on.

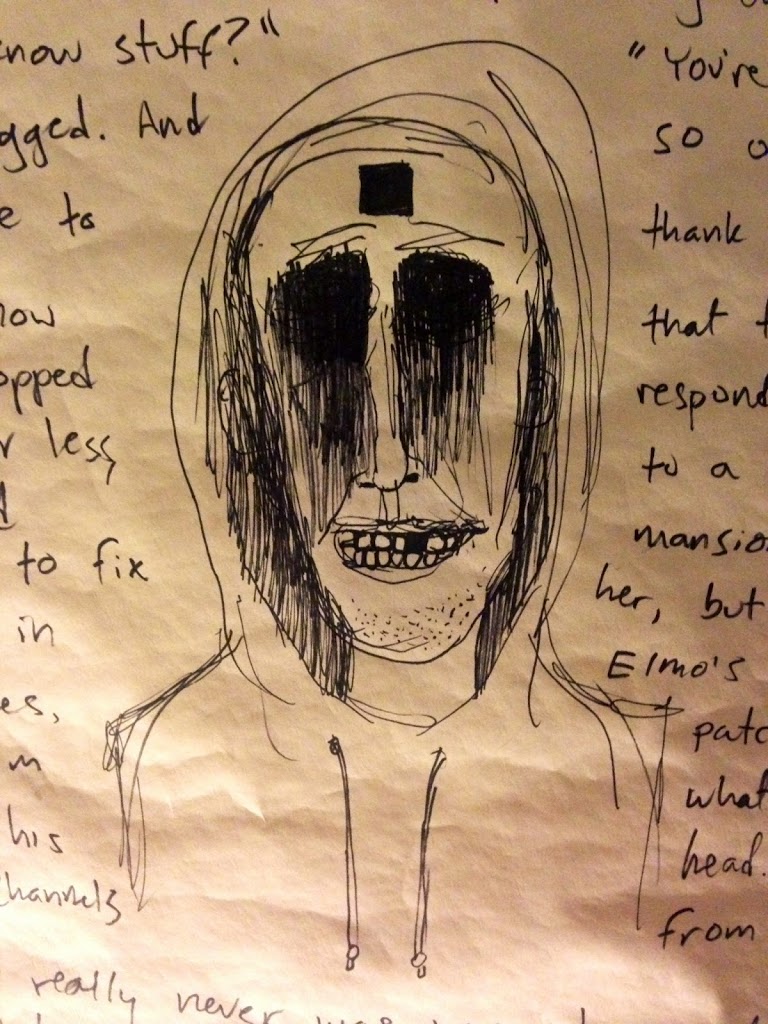

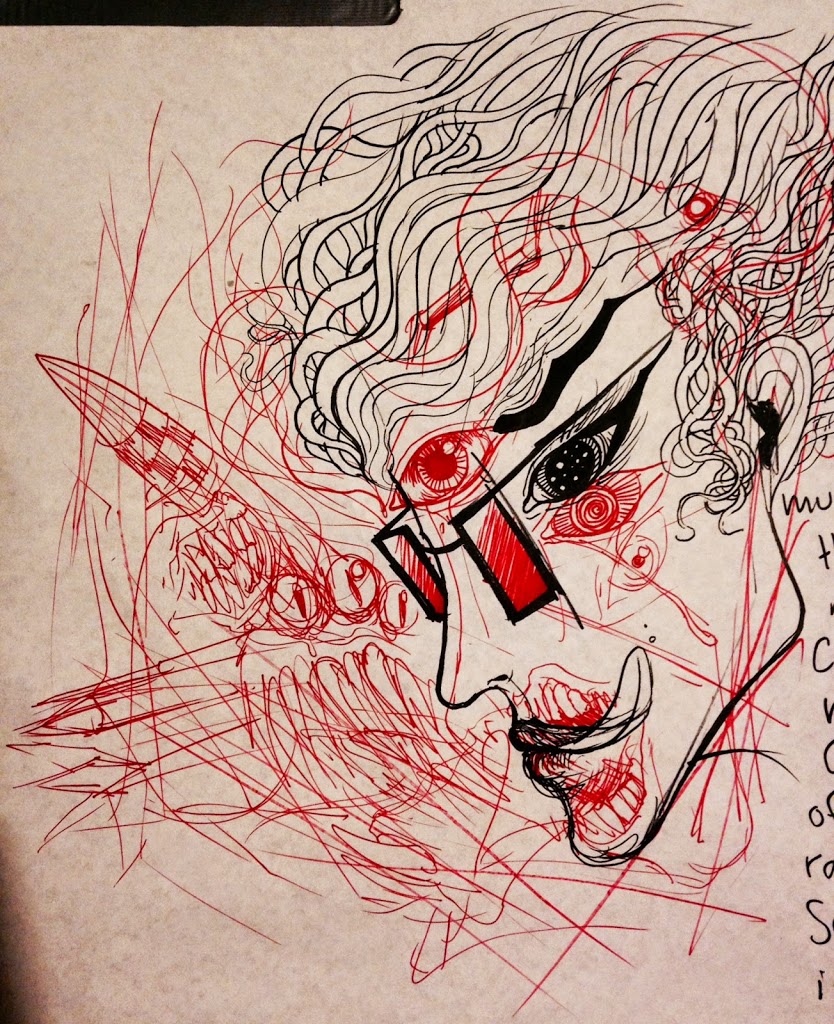

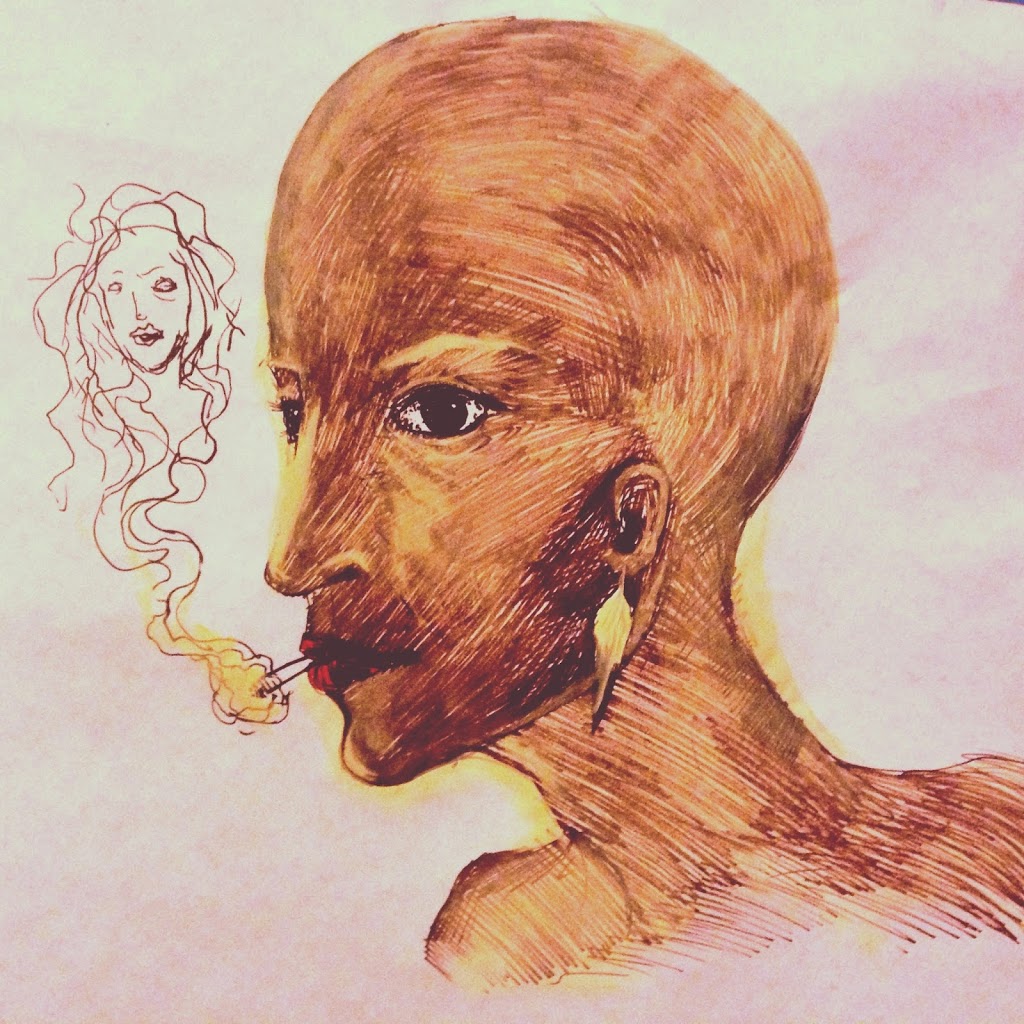

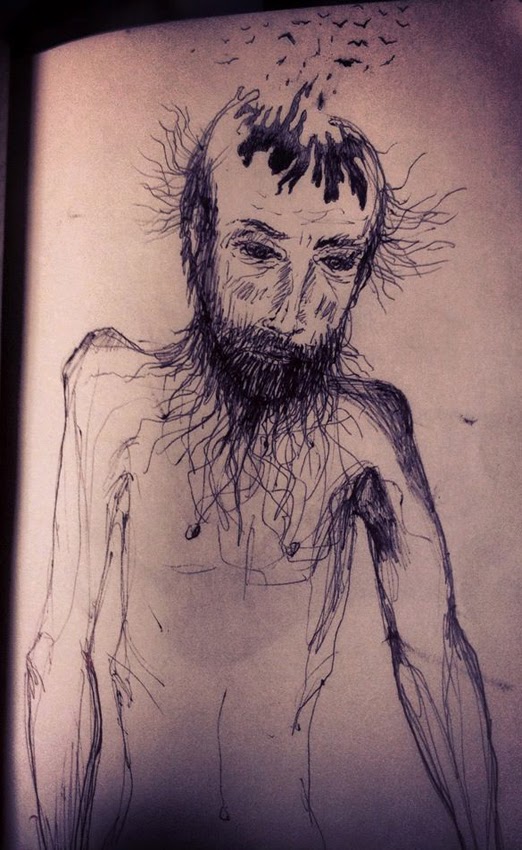

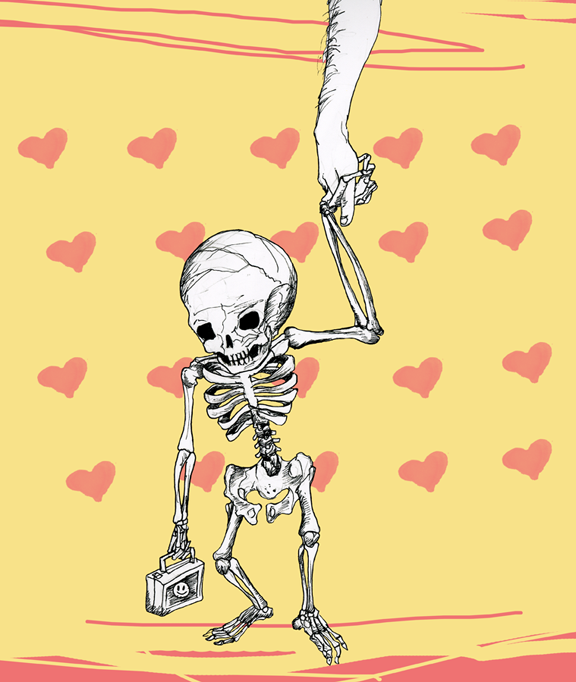

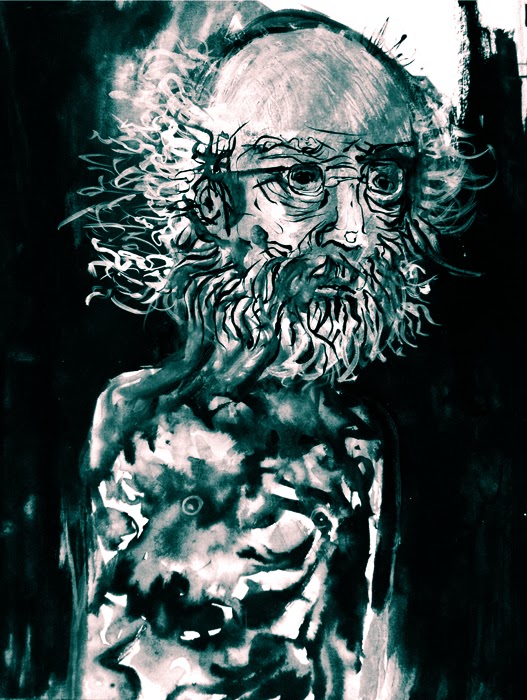

These days, Elmo’s sister has cause to thank him for his trust and for his fairness, now that the nerves inside her arms and legs and face and hands have stopped responding to her orders and she’s reduced, more or less, to a frustrated voice shouting in a condemned mansion of meat. They don’t have the tech yet to fix her, but they do have the tech to put a camera in Elmo’s forehead and network it to her eyes, patch her voice into his ears and give him what she always said he lacked – a brain in his head.

He had to lose his eyes to keep the channels from overheating, but he doesn’t mind. He really never was very observant. Now his sister describes to him what he sees, editorializing and guiding. And if ever anyone comments on the blackened, empty sockets he shrugs, smiles, and says “Hey, it’s not like I can see ’em.”