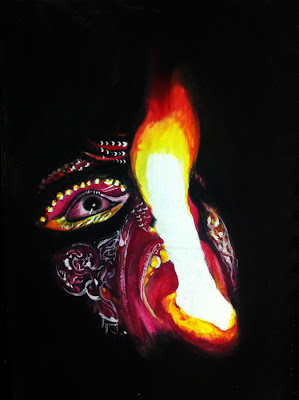

Jenny’s a champ. A real pro. She punches like meteors and dodges like a hologram, unless her manager asks her to throw a fight, which she does without blinking. Doesn’t blink much, period. One of the things people find odd about her. That, and the fact she actually seems to crave concussions.

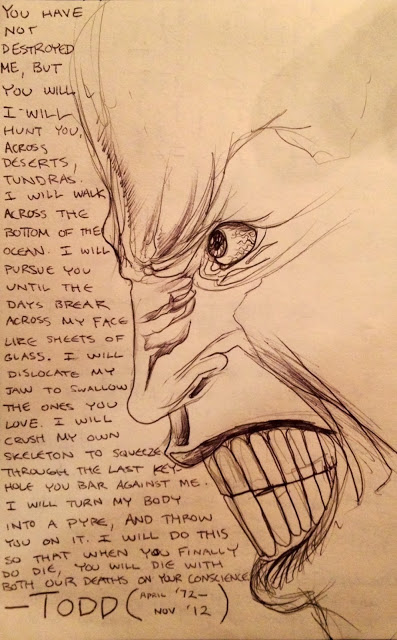

On those nights when she’s scheduled to lose, Jenny leads with her face. She blocks with her face. She makes sure the opposing punches can’t land anywhere but her face. She can go down in the first round if need be. The only challenge for the bookies is making it look like a fair fight. On those nights, Jenny stumbles drunkenly to her locker room, arm draped over her manager’s hunched back, and while he washes the blood out of her scalp and eyes, she sits at a folding metal desk and writes poetry.

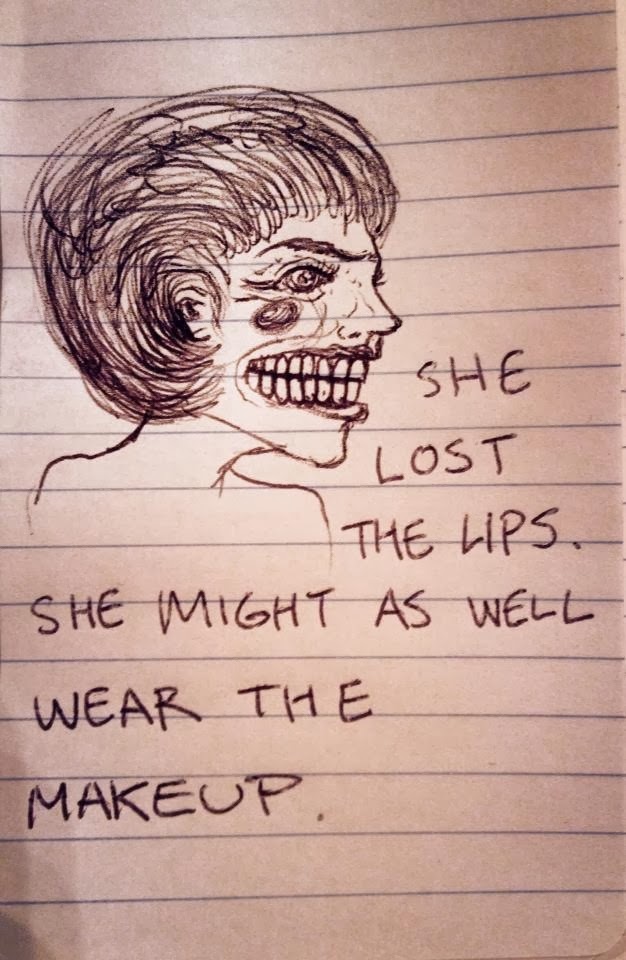

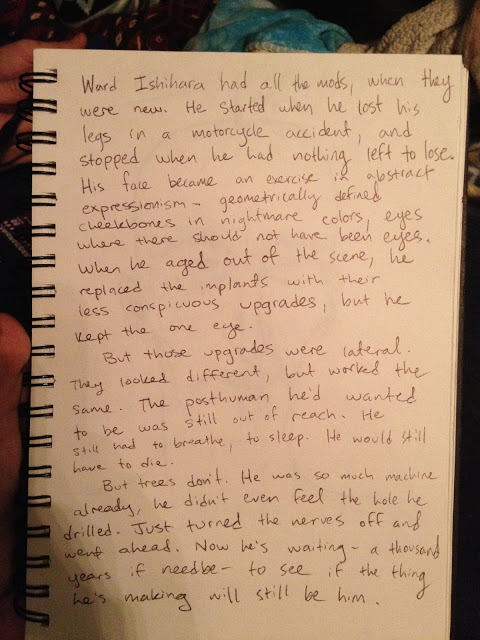

She writes in black composition books with wide-ruled lines. Her handwriting isn’t what it was when she started the project, and that’s part of the point. Jenny’s tried drugs, tried meditation, tried travel, and found that the altered states produced by these had already been explored by previous generations of poets. Wholesale brain damage is all that’s left to try. So she absorbs inspiration in the form of impact, and writes a revolutionary mosaic of clotted blood and shattered bone.