Rocketface doesn’t just win, he dominates. Some say that it’s because he only plays at stuff he can win, but the truth is that it’d be damn near impossible to find a contest Rocketface can’t win

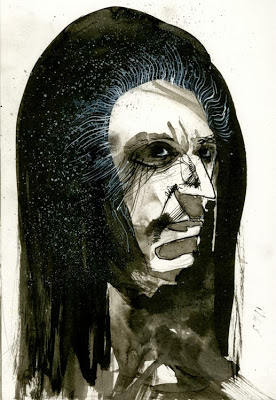

He was born fully-grown, the miraculous offspring of a derby girl and a jet engine. He’s got nitro for blood and hair product for hearts. That’s right, hearts – he’s got three of them: one for his body and one for each of his fists. One time, a hydraulic mining robot challenged him to arm wrestle. He crumpled it up and fed it to his hair.

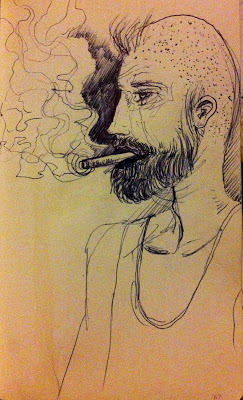

He can drink ten barrels of Sirian Supergin and keep drinking. He can eat rat poison and shit plutonium. He can hold his breath at least three minutes in hard vacuum – he could’ve managed at least a minute more, but his opponent had already been dead a while. When he dances, grown men weep.

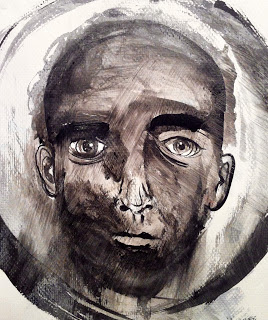

This is the point in the biography where the tone shifts, where we learn something about our subject that undermines his invincible image. There is no such thing to learn about Rocketface. He will continue barreling joyously across the galaxy, winning bets and turning the tides of wars, until he finally manages to find something that can kill him. And when he does find that thing, whatever it is, it’ll be so preposterous and noteworthy that merely encountering it will count as a win for Rocketface. That’s how hard he wins: he even wins at losing.