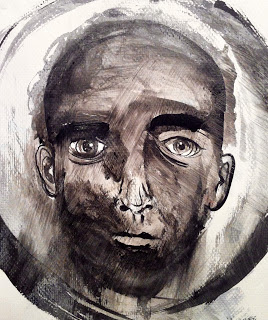

Arthur Molina is an unusually serious child. He insists that his mother cut his hair to precisely the same length every two weeks, and when people ask him why he’s always frowning he tells them that’s just the way his face looks. There is a reason for this.

Arthur (“Arturo” by birth, but he won’t let himself be called that) is an empath. He is uncannily good at reading emotions. He would be alarmingly good at it, except that he has yet to reveal his talent to anyone who might be alarmed by it. He doesn’t need to. He needs no outside corroboration to confirm his gift.

He is old enough to speak, but young enough to remember when he was born. The nurse placed him gently in the incubator. Too gently. Arthur’s newborn nerves detected the tension in the nurse’s fingers as she lowered his tiny body. She was trying not to cry. He cried for her.

He cried a lot, for a long time. He was devastated by the way the mailman gingerly dropped letters through the slot. Moved to tears of joy by the healthy gleam of the garbage men. He knew which of his classmates’ parents were going to get divorced before he knew what divorce was. His parents took him to a therapist, because of all the crying, and he sensed such an utter, terrifying coldness in the therapist that he resolved to appear sane from that day on.

On that day, Arthur closed his face. He suffocated the telltale twitching of his hands. His hair, which he’d been growing out for years, he let be cut. The world is an exhausting cataclysm of emotions for him, and he is determined not to make it worse with his own. He knows every avenue through which his feelings might escape, and he has bricked them all up until such a time as he is ready to explore them again. In the meantime he’ll become a doctor, or a police officer, or perhaps an advertising executive. Perhaps an artist, if he gets desperate. Anything, really, to pass the time until the walls come down.