You think you’re better than that guy, huh? You think if you’d been in his position you would have wondered about the swarming in your head, gone to a doctor maybe? Bombarded your skull with radiation, piped nitrous oxide in through your ears and snorted ammonia to flush out the invaders? Do you? Do you really? Well if you’ve got time to pass judgement on the poor bastard you’ve got time to hear his story.

Truth is, towards the end of it Carter didn’t have the space left in his head to wonder about what was taking up the rest of it. And before that he was in love. The kind of un-checked deadly love only hermits fall into. You can be a hermit in a city this size – one of the nice things about it – as long as you live on the forty-sixth floor and order groceries on the internet. That was Carter’s life.

He made mobiles. Thousands of them. The room was thick with them. He liked the shifting forms, the false weightlessness. It was only natural he should love the birds. They came in through his open window to frolic among the mobiles. The pigeons were too fat to navigate, but the cardinals made a game of it. One cardinal in particular became Carter’s hermetic paramour. He would lie on his bed, watching the birds trace shifting patterns in the mobiles with their private wind, and this one cardinal, his love would perch on his pillow. She would whisper secrets in his ear. One per day. And they would lull him into sleep.

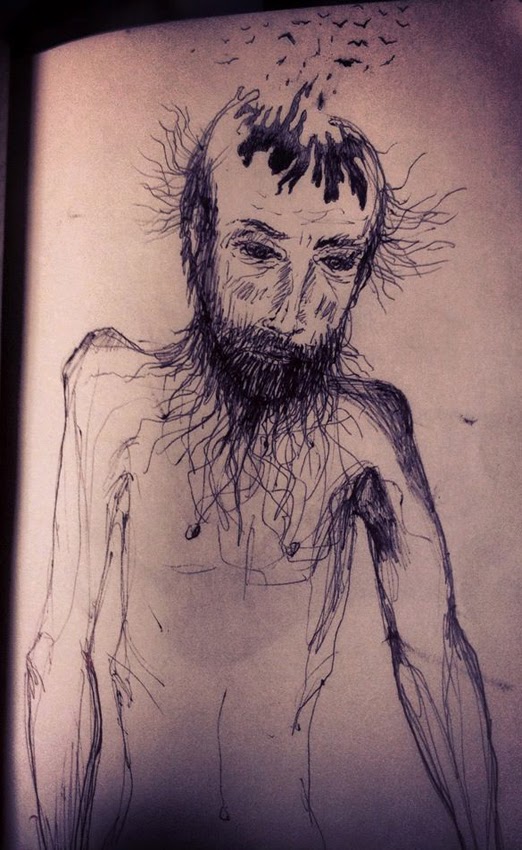

The secrets were in bird language, and they were meaningless to him. He could only tell that the messages were secrets, but could not fathom what they contained. What they contained were birds, tiny birds, which roosted in the folds of his brain and crowded out his human thoughts. He stopped making mobiles. There was no more space for them anyway. He would stand for hours at his window, imagining flight.

Eventually there was no more room for imagining. He leapt. His skull cracked. The birds flew out of every terminal part of him, suspending him for a moment above the sidewalk with the collective beating of their wings. When he touched ground it was as if he had been placed there by the same hand that places fall leaves upon the grass.

We could drive ourselves mad debating whether this was what he wanted. He’s got nothing left inside with which to tell us. But let me ask you this: don’t we all want to bring something strange and buoyant into this world? And isn’t flesh a paltry price to pay?