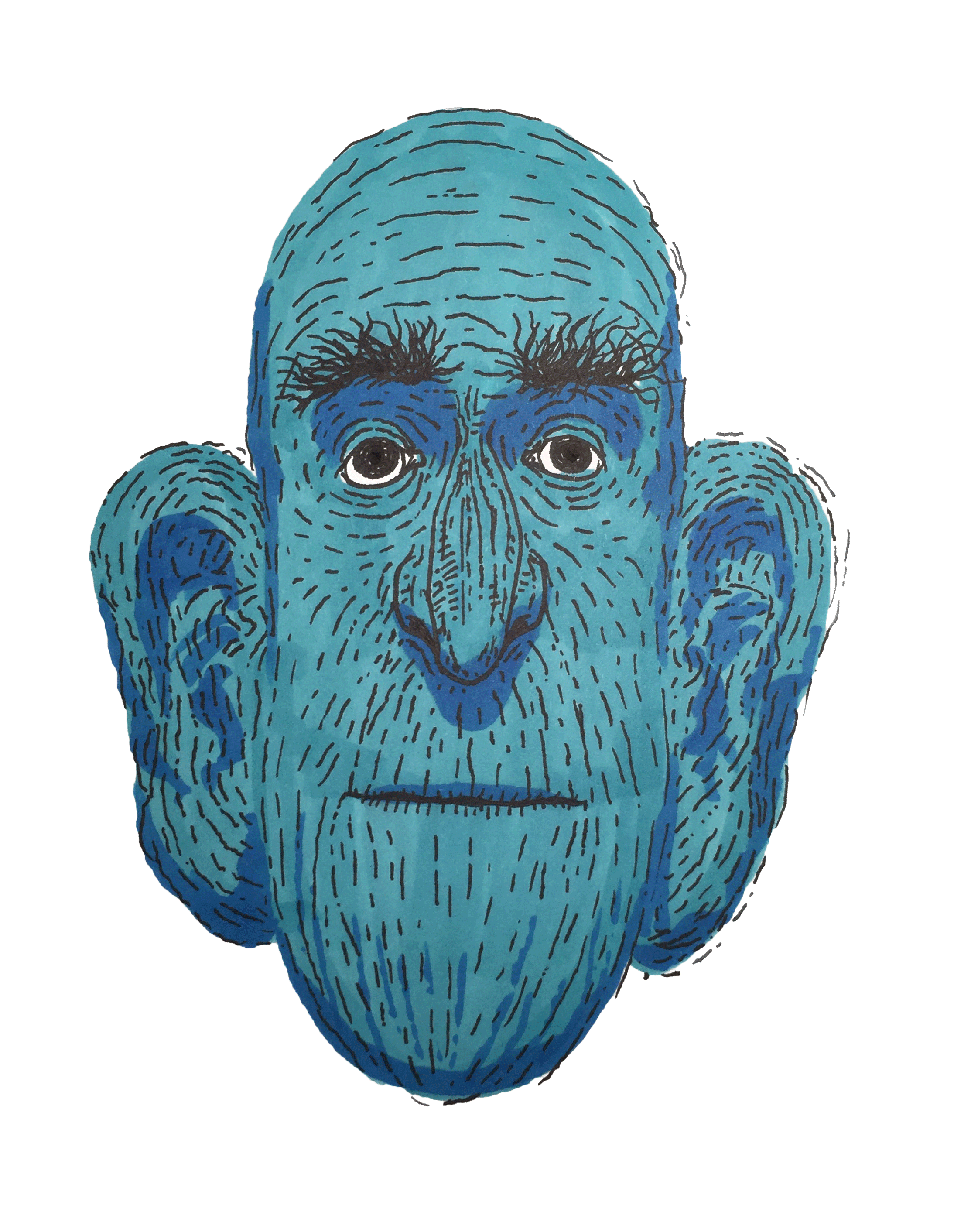

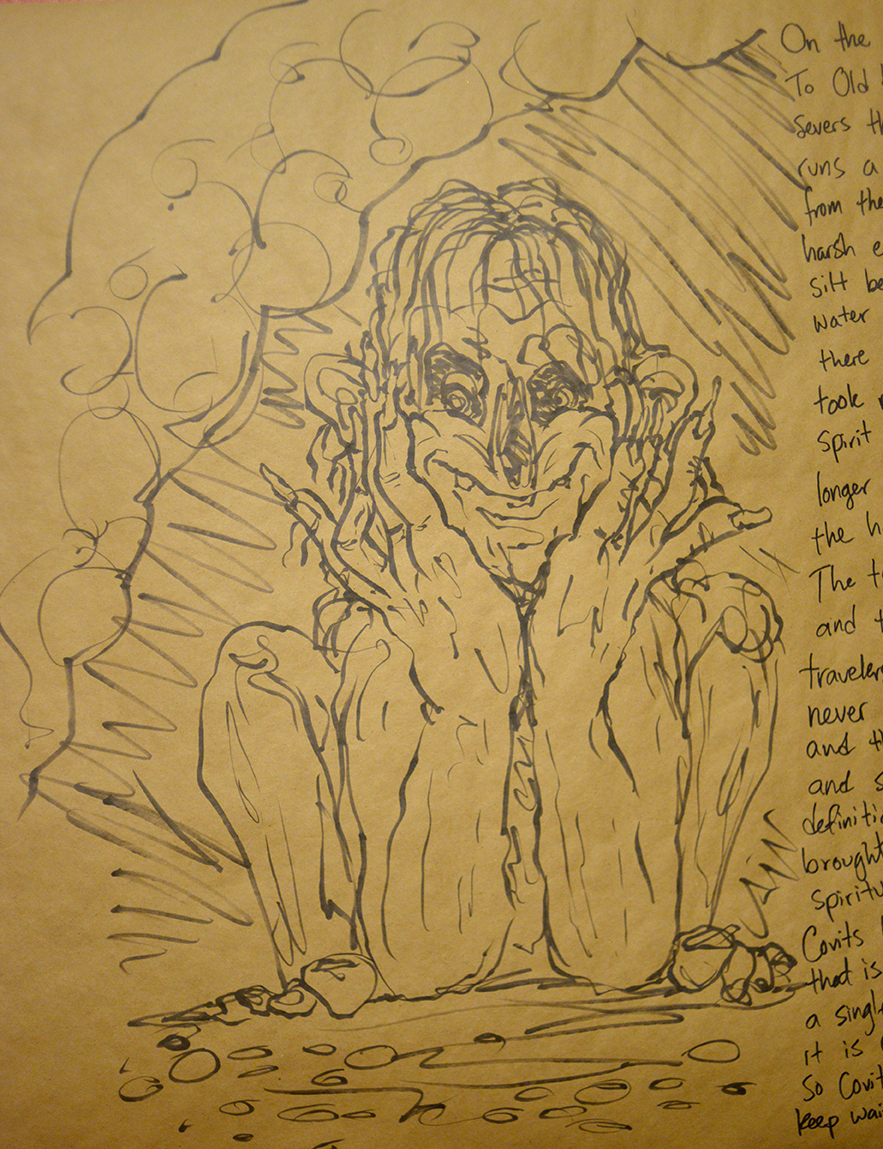

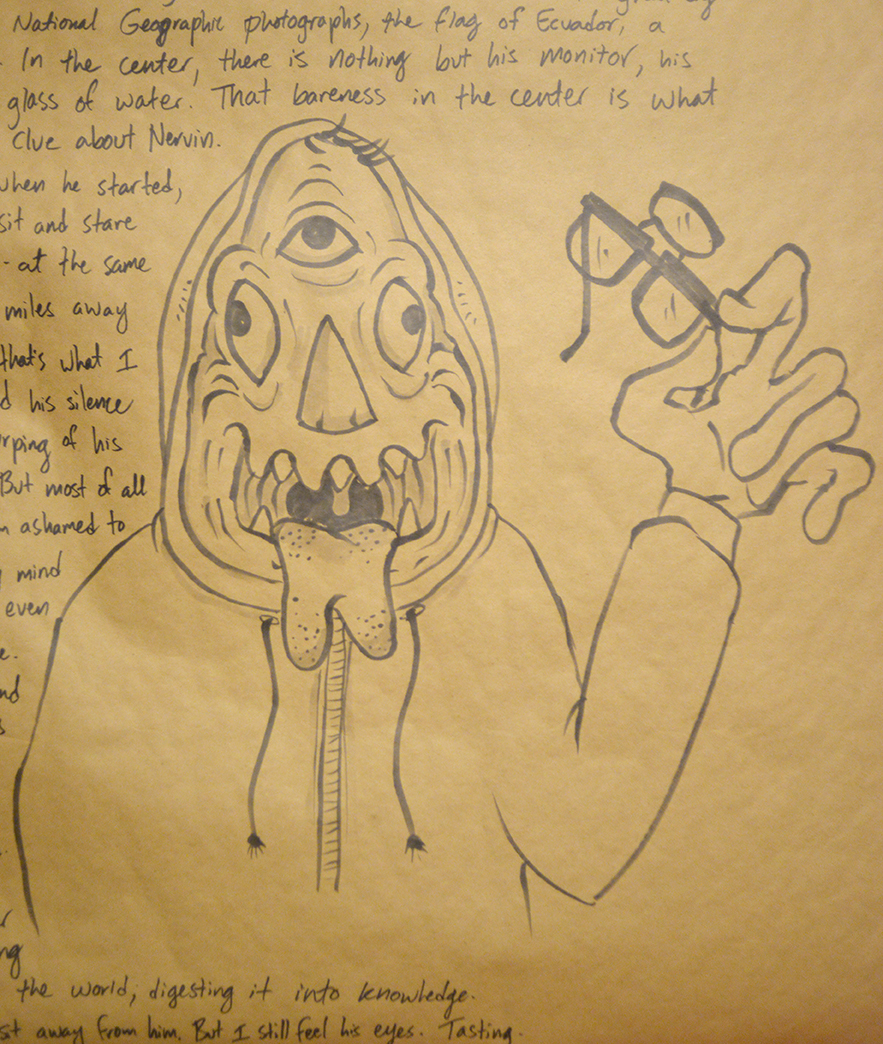

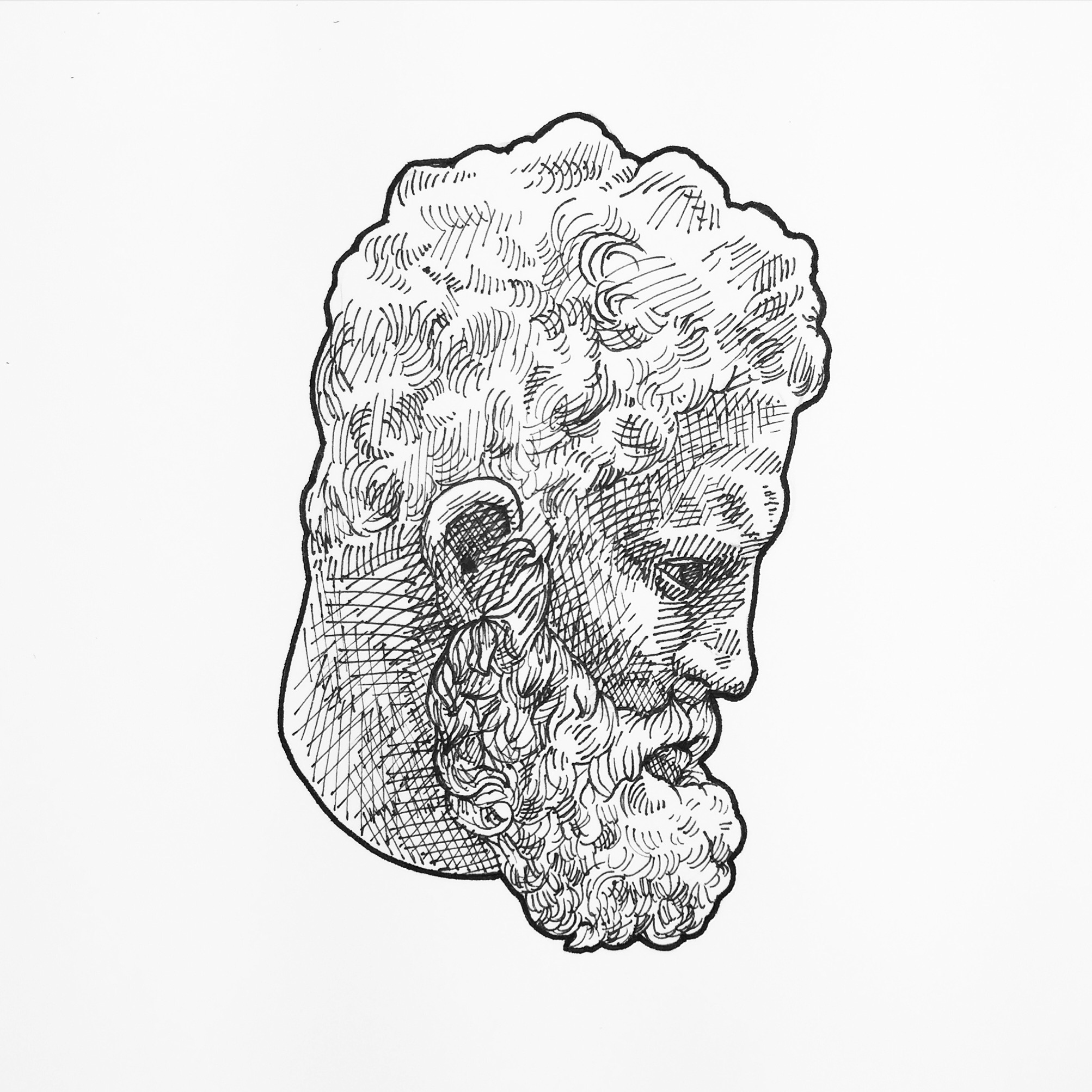

Fairoaks is a self-taught professor of ecology. His ears are huge, elastic, and so sensitive that when an airplane passes overhead, Fairoaks can hear the

passengers conversing. He is nine feet tall, his skin is blue, and he always wears the same green tweed jacket with the same brown suede elbowpads. But what makes Fairoaks special is this: only one person in the whole entire world can see him.

The person is a little girl named Emily, and Fairoaks is her private tutor. He tells her of the green things her citybound life prevents her from ever seeing. He sits on the edge of the pot of aloe in her living room – he is tall, yes, but very very skinny – and describes forests where the spaces between roots are other roots, and leafy creatures fight a slow, mortal dance for drops of sunlight. Emily wants to go to those places, but Fairoaks cannot take her. He fears the anger of her parents, he says. Fairoaks has no parents and Emily, being young, envies him this.

When Fairoaks is not with Emily, he is alone. After all, no one else can see him. The other tall, thin people – with whom he used to dance a manic jig to complement the forest’s slow one – died long ago, or at least ceased to be visible to one another. On nights when Emily has friends over, or when she is in a foul mood or away on a field trip, Fairoaks visits the old glens. On those nights, he sleeps swaddled in his ears, and tries to imagine the dreams his charge is having.