To be a town, you don’t need all that much. You don’t need plumbing, long as you’ve got a river and a bucket. Hell, if you’ve got those two things you can pretty much do without a fire department too. Electricity’s a shameless extravagance, and you can get by without cops as long as folks are generally decent, or so thoroughly horrible as to guarantee mutually assured destruction. But if you ain’t got any of those other things, there is one element that you absolutely do need: you need a Lester.

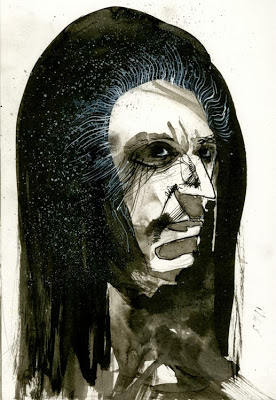

We call him “Babyface,” because he’s got one. You can search and search that round head for wrinkles, and all you’ll turn up is a lazy eye and a hole where a nose used to be. This thanks to the fact that the nerves in Lester’s face are all dead, the way Hollywood models pay to have done. There’s no electrical signals to tell Lester’s face to age, or to do anything, really. And he’s our hero.

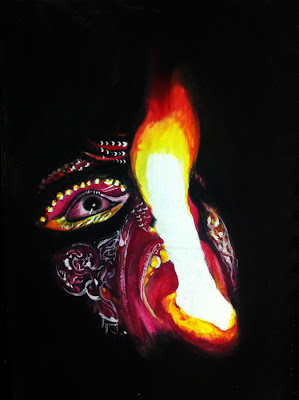

Eighteen years ago was when a gasket burst on the vat of high-pressure phosphene gas Lester was cleaning at The Plant. Paralyzed everything between the hair on his head and the hair on his chest. Rotted away his vocal chords when he breathed in, and his nose when he breathed out. And the smug bastard just turned on his heel, gas still reaching for the high ceilings, walked to the break room and punched out.

See, The Plant budgets for this kind of thing. End up paying settlements to two or three employees a year, just to keep things running smooth. Lester couldn’t see too well after the accident. He couldn’t smell, taste, or talk. But he could hear fine, and his future sounded like a god-damn cash register.

They gave him a hell of a lot more than they give any of us what actually work there. And he gives it right back to us. Sits stiffly at the pockmarked bar in the Blue Tip, night after night, buying drinks and listening to stories. Folks come from all over town with their troubles, and he buys ’em off them. People say he’s a martyr – they see suffering in those wilted eyes of his. But I know better. His face is only frozen in that frown, and he’s got no idea what his eyes are doing. Cause lemme ask you something: If Babyface didn’t get the joke of it all, why the hell would he wear his hair that way?