Rob Washington makes terrible cakes. They are spongy, but never moist. They are slightly more flavorful than wet cardboard. The frosting is so sweet it makes teeth burn. By all rights, Washington’s Bakery should have closed years ago. But although Rob’s baking is miserable, his hugs are legendary.

The counter behind which Rob stands has a section that can be folded down to allow Rob into the eating area, or fixed in place to prevent customers from passing through. It is never fixed in place. Rob’s great deficiency as a baker (or anyway, one of his deficiencies) is that he has no sense of smell. Yet he can smell despair before it even walks through the door. He’ll have a cup of coffee ready by the time the little silver entry-bells are done ringing, and by the time you’re at the counter, he’ll have crossed around to meet you. He rarely says anything. If he does, it’s something simple like, “Oh, honey.” Something that carries no meaning, just the soothing bass of his voice. Then he enfolds you in his hamhock arms and doesn’t let go until he’s wrung the sadness out. After that, you’ve got to buy something. He won’t force you, but you know you have to.

And so Washington’s Bakery is full at all hours, every table packed with people gamely struggling through their cakes as a show of gratitude. The tables are small and scarce, which means the bakery has been responsible for a lot of chance meetings. Some of those have become marriages. There’s a general camaraderie amongst the patrons, even if they never speak. Something about having the sadness bled out of you by big arms, then suffering through baked goods in solidarity.

Rob must know the real reason for his success. What other Bakery have you ever heard of that’s open 24 hours? He sleeps on a cot behind the counter when it’s slow, always ready to leap up at the sound of the bell. The customers are so wrapped up in their own problems, they hardly ever question why a grown man would choose to spend himself on such an endeavor. If anyone ever asked, Rob would tell them it’s for more than just the love of the world.

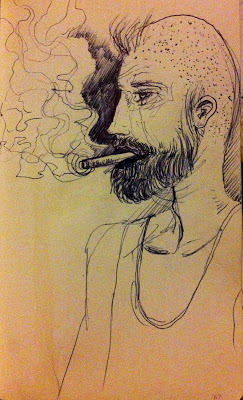

“I know my cakes are terrible,” he’d tell them. “If anything, they’ve gotten worse over the years. What I’m waiting for – and maybe you’ll think this is silly – but what I’m waiting for is a handsome man about my age, with clean fragile hands and redeemable eyes, who comes into my shop crying. And when I hug him, and he finally smiles, he’ll tell me:

‘God, this cake is terrible. Let me show you how to make a better one.’”