Maya Rios takes care of people. Always has. Maybe it’s a function of being the firstborn in a litter of seven, with parents too busy taking extra shifts at the restaurant to take care. That would be the standard explanation. The more likely explanation is impatience.

Maya never seems impatient. She has taught three children of her own to walk, and talk, and poop in the proper receptacle. She waits in pediatrician’s offices, on soccer sidelines, in airports for airplanes that will take her to visit her aging parents, who she also takes care of now. Her apparent serenity comes from the fact that she is never waiting on another person’s decision. The decision is always hers.

The only place her impatience bubbles to the surface is in the online poker games. No one in her real life knows she plays. One of her brothers introduced her to the idea, and Maya scolded him until he promised never to play such foolish games. She plays in the grey hours of the morning, while her house sleeps. There is no risk of her husband or children waking up and surprising her; she is everyone’s alarm. It is just as well. They would not recognize her if they saw.

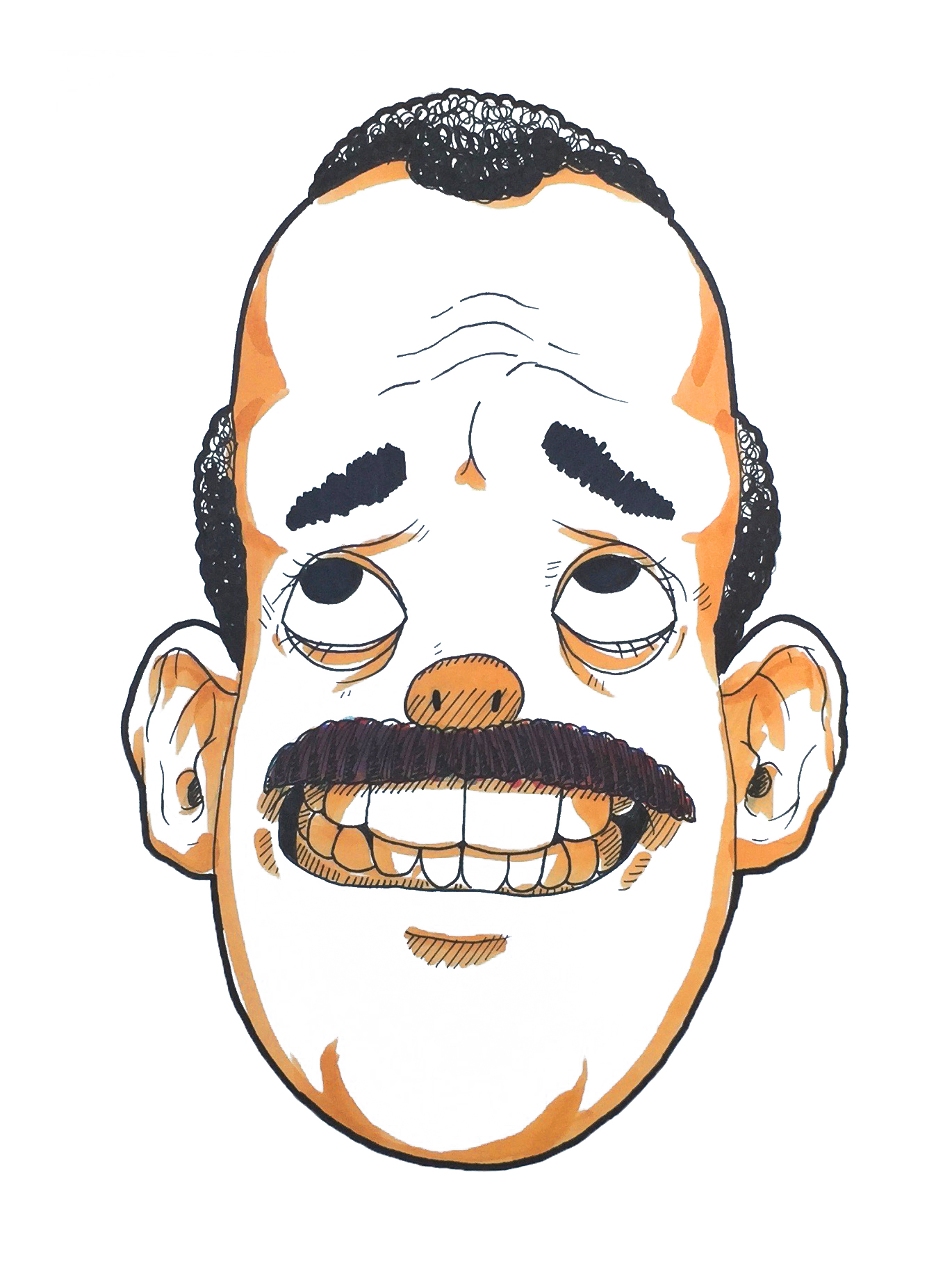

As she waits her turn to call or raise or fold, her lips maintain a constant snarl. Her decision has been made for minutes now, and waiting for the others only delays her inevitable victory. She chews her lips as she waits for the new cards to be dealt, daring the random number generator to defy her.

Maya has netted hundreds of thousands of dollars on these illegal poker tables. Her username is a legend, and some servers even ban it. She uses the money to give her children the life she wishes she’d had, and lets her husband think he makes enough to pay for it. Why shouldn’t he believe her? After all, she takes care of all the bills.