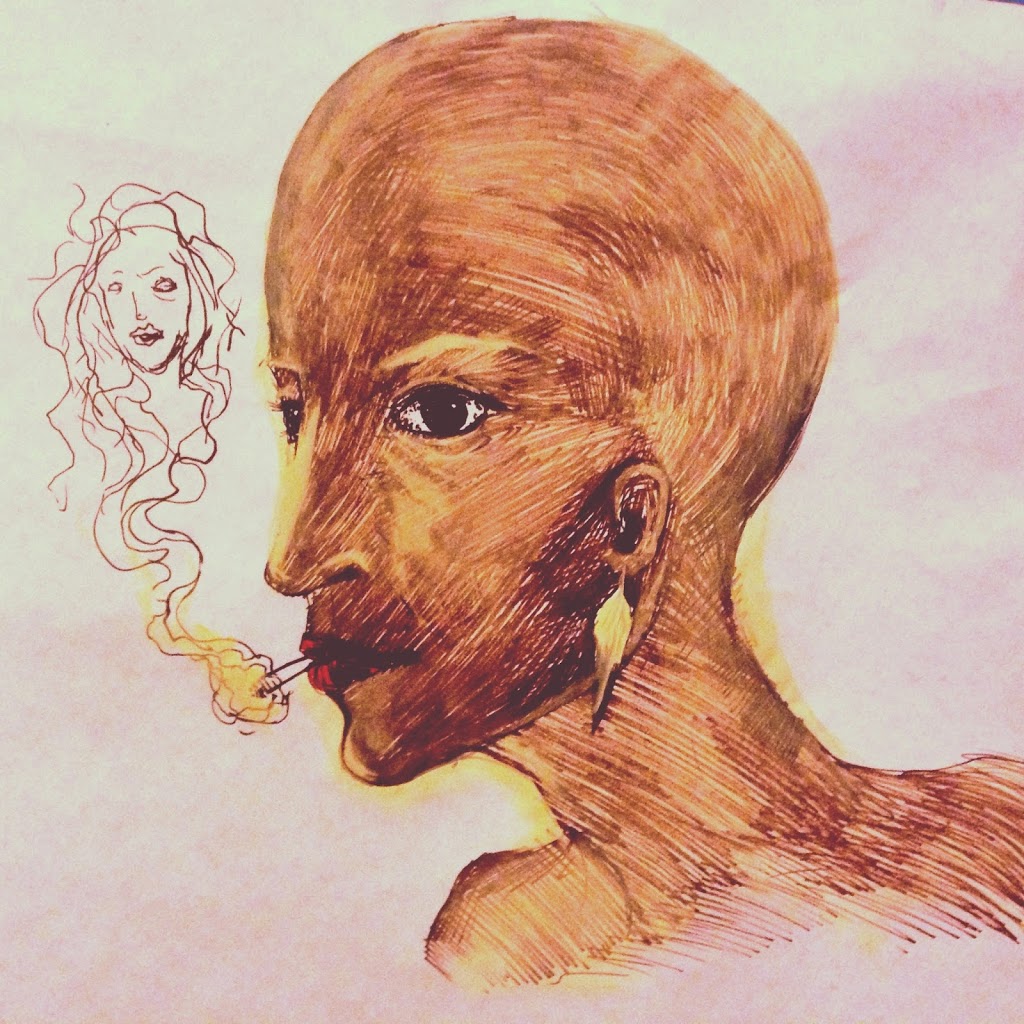

Now, don’t get me wrong, Cassandra is a lovely person, just lovely, and you can’t argue with results, I just … don’t think she should be working for NASA is all. You don’t know her methods like I do – must not know, if you’re thinking of hiring her. So let me set the record straight: Cassandra Streng has no methods. Go ahead, lift he hood of one of those legendary formula 1 racers she’s so proud of. See if you can distinguish the engine from a bowl of steel spaghetti. She’s a master of non-euclidian mechanics. The geometry of her engines would drive whole pit crews insane, if her cars ever broke down.

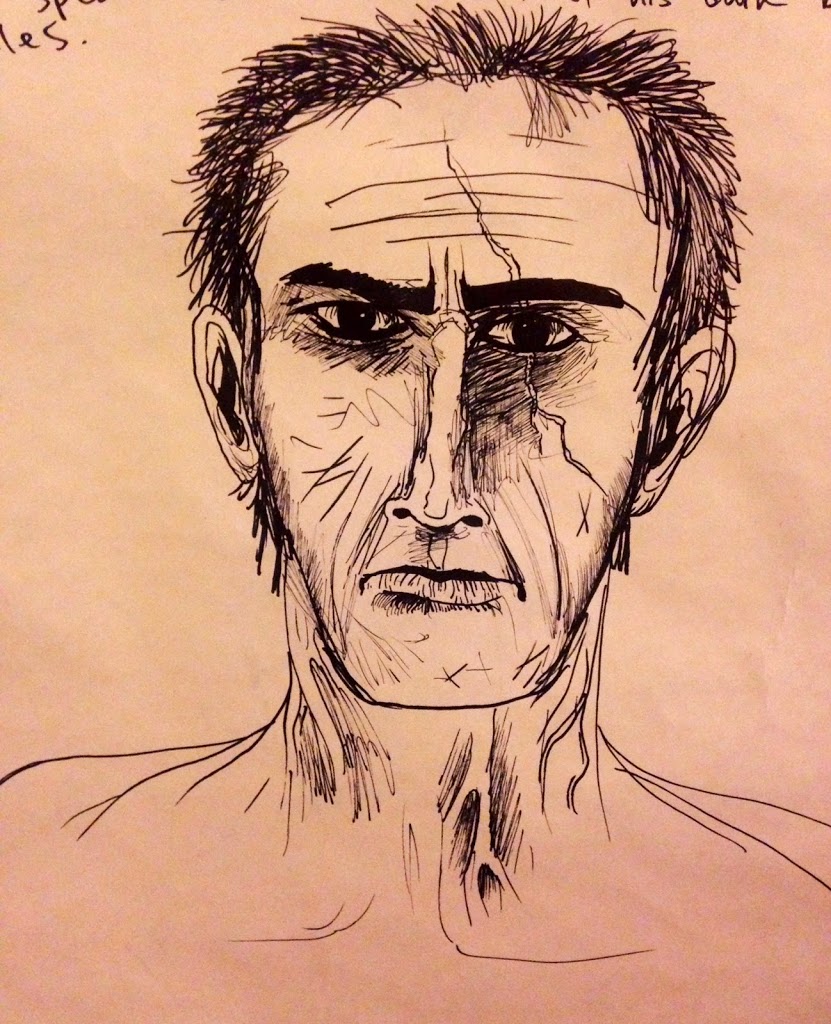

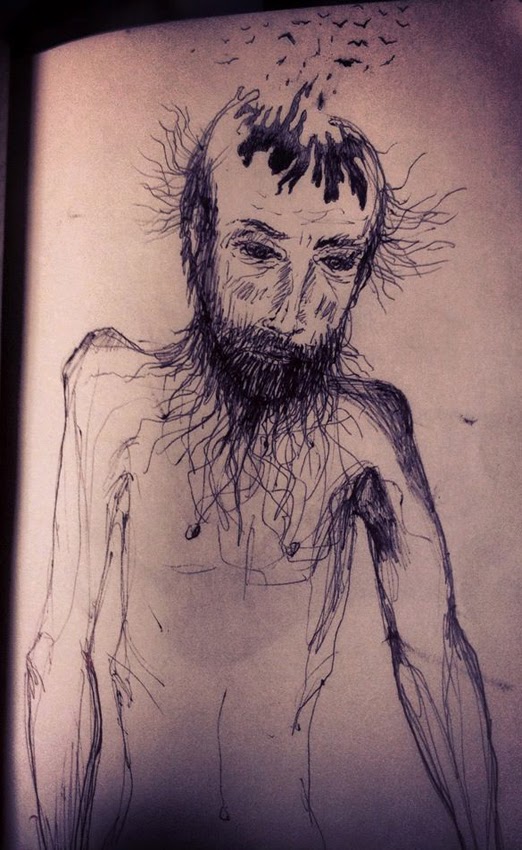

But they don’t. They break records, the sound barrier, a neck once due to unhealthy acceleration, they break every possible thing except for down. Why? How can a red-hot knot of scrap metal and aluminum tape produce these results? The answer is, no one knows. And as a potential employer, that should disturb you.

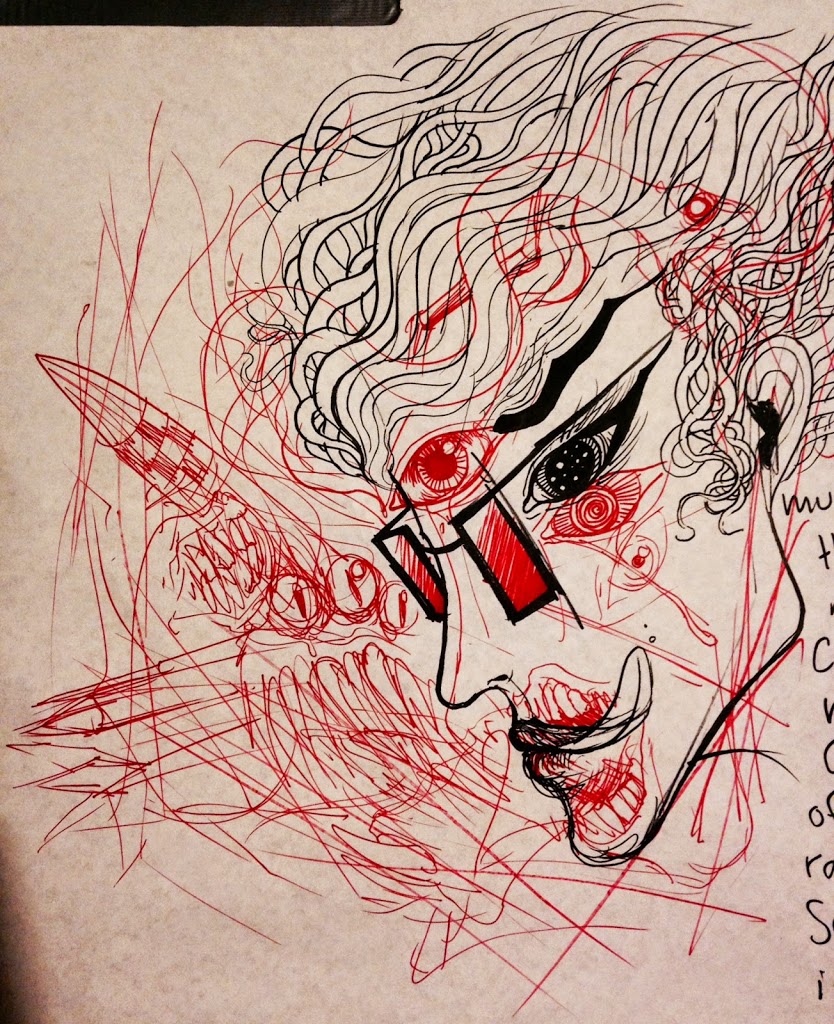

I tell you this as a trained engineer, a concerned citizen, and a good Christian: I have gazed into her manifolds and seen Satan staring back at me. She will get your men to mars, I have no doubt. But what demons will be traveling with them?