Archibald Skol has already lived longer than he intended. Longer than most of the other children in his war-torn corner of the world. Longer than his parents, though that wasn’t hard – his mother died in childbirth, and his father did something to upset a firing squad shortly after. Archibald was raised, tutored and protected by two forces that war within his stomach: a bottomless hunger, and a desire to die.

Archibald became the dictator of his own little chunk of hell simply by being willing to take the risks a sane man wouldn’t. Even after seeing him lead his militias into rifle fire, eat his own poisoned food beside the enemies he was poisoning, wager an entire province in a game of Russian Roulette, his enemies assumed there must be some cost they could impose on him high enough to make him stop and negotiate. There was not.

He soon ran out of family for his enemies to abduct and torture. He ran out of enemies almost as quickly, though they reproduced. He ran out of friends as well, though he never really had any friends. He prefers carnivorous animals to people – his only friends are his hyenas and sharks and crocodiles – and when one of his crocodiles was stolen and killed and its entrails flamboyantly displayed, he simply bought a new crocodile and gave it the same name as the old one. The crocodile was immortal, as Archibald himself seemed to be.

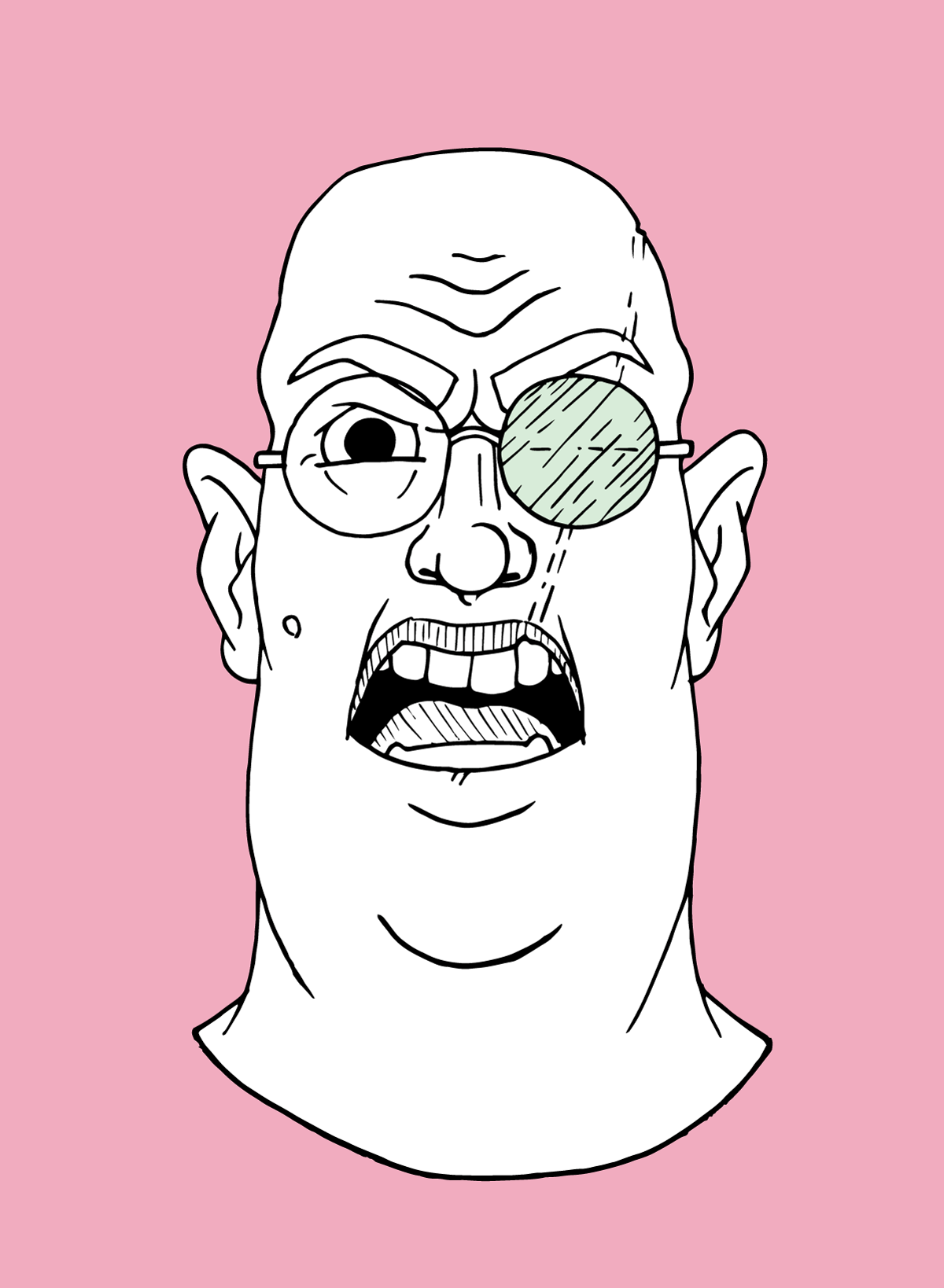

As he grows older and more powerful, his schemes grow ever more elaborate. He wants to hold the rain hostage. He wants to design a weaponized termite. He wants to turn every diamond ring in the world into a homing beacon for his fleet of military drones, so that every happy couple must turn over their jewels on pain of death. The people who try to stop him these days are a different breed than the petty despots he murdered in his youth. These men and women have miraculous powers; abilities that would let them snap his neck with a thought, but they never do. They too seem to believe there is some cost they can impose so high that it will discourage Archibald from striking again. But everything they take from him – his ring finger, his eye, his caribbean fortress – is simply something they can never take from him again.

Archibald grows weary of these games. He meant to burn twice as bright and half as long, but now has burned both bright and long, and is in danger of burning out. The jewels and delicacies with which he stokes his furnace will not sustain him forever, he hopes. He is ready for hell – he grew up in it. There is a certain nostalgia there. And if he has to build that hell on earth to finally return there, then so be it.